Mapping the Landscape of FQHC Sites in Pennsylvania from 2020 - 2025

What Are FQHCs and Why Do They Matter?

Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) are community-based outpatient clinics that provide comprehensive primary care services to individuals regardless of their insurance status or ability to pay³. Established under Section 330 of the Public Health Service Act, FQHCs are designed to improve access to care in medically underserved areas and among vulnerable populations. In addition to primary and preventive care, FQHCs offer enabling services such as interpretation, transportation, and case management to address social and logistical barriers to care.

While the terms Community Health Center (CHC) and Federally Qualified Health Centre (FQHC) are often used interchangeably in literature, a CHC is a nonprofit clinic serving underserved areas, and most CHCs are FQHCs, but not all are; however, FQHC is a community health center that meets federal requirements to receive special funding and reimbursement.

To qualify as an FQHC, an organization must meet stringent federal requirements regarding service scope, quality standards, governance, and accessibility. A key feature is the requirement to operate under a governing board where a majority of members are patients; ensuring the center remains responsive to community needs. FQHCs receive federal grant funding from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) and benefit from enhanced reimbursement under Medicaid and Medicare through the Prospective Payment System (PPS). This financial model is crucial to sustaining care delivery in high-need and low-resource communities.

What Are FQHC Look-Alikes?

FQHC Look-Alikes (LAL) are health centres that meet all federal requirements of a full FQHC but do not receive Section 330 grant funding. Despite this, they are eligible for PPS reimbursements, 340B drug pricing, and National Health Service Corps eligibility for their providers. These centres often function similarly to FQHCs in their community presence and structure, but must operate with fewer federal resources.

Do FQHC Look-alike become FQHC overtime? Health Resource and Service Administration (HRSA) data does not show FQHC Look alike becoming FQHC in the past 5 years (2020-2025). However, FQHC Look-Alikes do not automatically become FQHCs over time. While Look-Alikes are similar to FQHCs in many respects, they are not considered FQHCs and do not receive the same level of federal funding or other benefits. Look-Alikes can continue to operate as such and may choose to pursue FQHC certification or funding opportunities if they wish to receive additional benefits¹.

How Are FQHCs Organized?

Each FQHC is a health organization that may manage multiple service delivery sites under a single HRSA-assigned ID i.e. BPHC Assigned Number. These sites can include permanent health centres, school-based health centers, mobile vans, seasonal facilities, and more. In HRSA data, these are captured as individual service locations but are linked to one umbrella organization responsible for reporting and compliance.

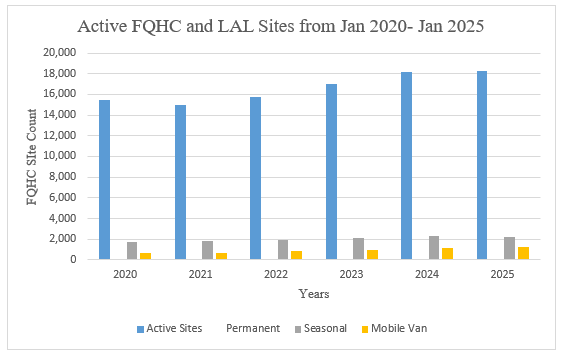

FQHC Growth from 2020-2025

According to Health Resource and Service Administration (HRSA) data, the growth in active FQHC and LAL sites from January 2020 to January 2025, the total number of sites increased steadily from approximately 15,000 in 2020 to nearly 18,500 by 2025. Permanent sites saw the largest absolute growth; Mobile and seasonal sites, while smaller in number, also trended upward indicating an increased focus on flexible and targeted service delivery models.

The upward trajectory reflects expanded federal funding especially following the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020-2021. But this national growth raises a key question: Where are these new sites being located and who is benefiting?

Visualizing FQHC Growth in Pennsylvania

To better understand how the FQHC & LAL landscape is shifting in Pennsylvania, we observe the following two maps:

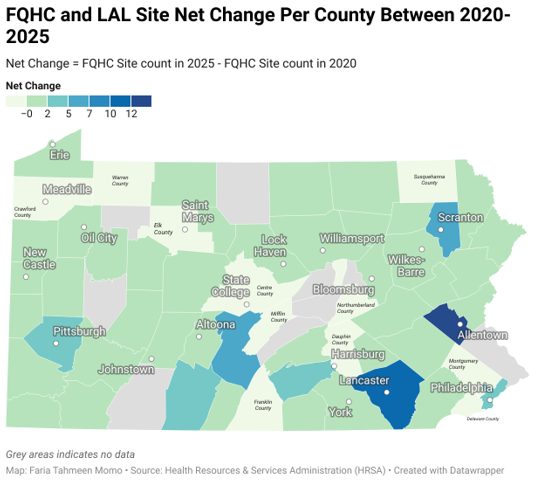

Map 1: Net Change in FQHC and LAL Sites, 2020–2025

This map captures net site growth per county, defined as the number of active sites in 2025 minus those in 2020. According to the Center's definition, there are 48 rural counties and 19 urban counties in Pennsylvania⁶.

As per map 1, the majority of FQHC growth occurred in urban counties like

Lancaster, Philadelphia, Allegheny (Pittsburgh), Lehigh (Allentown), and

Lackawanna (Scranton).

The Lancaster County leads the state in site expansion, with a net gain of over a dozen FQHC sites. Significant gains are also seen in Philadelphia, Scranton (Lackawanna County), Allentown (Lehigh County), and Pittsburgh (Allegheny County).

As per this map, rural counties, particularly in northern and central PA (e.g.,

Elk,

Warren, Centre) have negative net change meaning they have lost FQHC sites from 2020. Most of these counties includes Medically Underserved Areas/Populations (MUP).

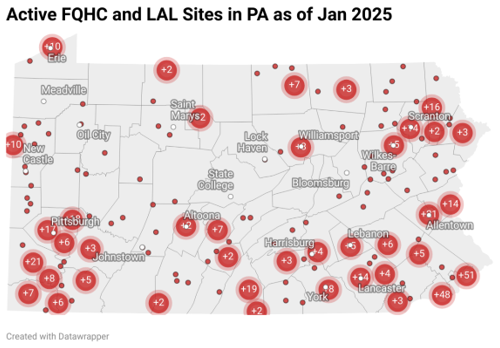

Map 2: Active FQHC Sites as of January 2025

Source: Health Resource and Service Administration (HRSA)

Each red dot on this map represents an active service site as of January 2025. The maps show that the urban areas are densely populated with active sites. Northcentral & north-western Pennsylvania remain under-covered, with large geographic gaps in care access.

Together, these maps illustrate a geographically uneven expansion of FQHC services. Urban and suburban counties are successfully scaling their FQHC networks possibly in response to population growth, increasing Medicaid enrolment, or targeted investments. Rural counties, in contrast, may be falling further behind, highlighting longstanding challenges in provider shortages, transportation access, and funding inequities.

This pattern mirrors national concerns. Rural FQHCs face greater operational instability due to workforce shortages, aging infrastructure, and rising demand². According to Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF), 383,121 people live in areas of Pennsylvania that are officially recognized as experiencing a primary care provider shortage many of whom rely on FQHCs for access of care⁵.

This spatial exploration raises critical questions such as:

(1) How can we better support FQHC expansion in geographically isolated and low-resource rural counties?

(2) Should there be dedicated rural funding tracks, or expansion of mobile and telehealth services in these regions?

(3) Are FQHC Look-Alikes a scalable option for rural counties with limited infrastructure?

(4) Are the communities most in need receiving the investments they deserve?

Future research should examine how site growth correlates with local health outcomes including opioid treatment access, maternal health services, Medicaid utilization, etc. FQHCs are foundational to Pennsylvania’s health system, especially in closing access gaps for vulnerable populations. As we move forward, we must ensure that no community is left behind.

References:

1. Becoming an FQHC or FQHC Look-Alike—Frequently Asked Questions answered by our FQHC Experts! (2020, September 21). FQHC Associates. https://www.fqhc.org/blog/2020/9/15/becoming-an-fqhc-or-fqhc-look-alike-read-this-first

2. Community Health Centers’ Progress and Challenges in Meeting Patients’ Essential Primary Care Needs. (2024, August 8). https://doi.org/10.26099/wmta-a282

3. Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) and the Health Center Program Overview—Rural Health Information Hub. (n.d.). Retrieved December 9, 2024, from https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/federally-qualified-health-centers

4. FQHCs and LALs by State. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://data.hrsa.gov/data/reports/datagrid?gridName=FQHCs

5. Primary Care Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs) | KFF. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/primary-care-health-professional-shortage-areas-hpsas/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

6. Rural Urban Definitions—Center for Rural PA. (n.d.). Retrieved from

https://www.rural.pa.gov/data/rural-urban-definitions